In bits and pieces: Some meandering commentary and distractions on and around Fiona Macdonald’s work in Melbourne’s artist-run initiatives

1.

It has ambition beyond it surface area. There is a triangle. A triangle that has narrative imbedded within it – it’s as clear as day but oblique as its angularity that it predictably performs in three goes. And like anything embedded this narrative is compromised and open to exploitation. Being stuck on a page that it mostly takes for granted is part hierarchical dimension of the situation – materially and compositionally. So comfortable and self-assured is the triangle of its place in the world that its presentational context doesn’t warrant a mention in this so-called hierarchy. Its surface smugness has its back to the wall – it can’t even imagine what might be happening behind the plasterboard that it is pinned to. To be fair this triangle on paper is rehearsed as a propositional space that can’t be realised. It acknowledges this condition not as a failure but as a part of an ongoing theoretical enquiry about the state of the world beyond the plasterboard and into the potential affect it might have on all surfaces.1

2.

It has too many choices They say it’s a niche for the public but as we all know quantitative scope is not what any niche has going for it. So this notion of a niche for all is a public relations fallacy that makes its barriers invisible or at least innocuous to passers-by who have no interest in entering. There are a few of those. The others are caught by a loop of interrupted desire that makes it hard to turn around and keep walking. This space is about a continual movement and gratuitous display. The shiny seductive surface that lines the niche is only there to be recaptured onto another surface. This commemorative documentation is soon scrapped as the surface of the niche is continually revaluated. The reviews are not kind. But that’s ok as the paper they’re printed on is used as the basis of the next surface. The text soon becomes illegible – it’s now a pattern. The reviews are not kind and so forth. So nothing is quite fulfilled, which is different from it being finished. This space is set up for the aspirations of the apsirational. As you could imagine it’s pretty crammed in there with all that jostling and reproductive technology. I think I could get very thirsty.2

3.

It once sat on a trestle table at a fete. There’s a degree of control that is inevitable when you grow a shrub in a medium sized pot. While quite capable of living within the confines you have chosen for it – the restrictions imposed on its root system will need to be addressed at some stage. You either need to repot or risk the dull and straggly growth to the compost. Nevertheless a planter box is built for a plant that would otherwise thrive in the ground – thrive in a noxious (promiscuous) weed sense of the word. It’s for this reason and its associations with institutional cyclone fencing that make this shrub an unconventional choice for a pot plant. The planter box made from treated timber hides the generic black plastic pot and is a marker of order in anybody’s yard. The box is modestly constructed and is only slightly elevated from the ground. It sits in view of the home’s entrance but just out of reach for it to be part of a daily habit of care. This and its grow-anywhere reputation resulted in the plant not being watered regularly. Then not at all. The potential to survive the hardiest conditions had only resulted in a forlorn grey brown death with only the most occasional budding that would be ignored while some house-guest butted out another cigarette at its base.3

It’s not my intention to rearticulate Andrea Fraser’s position in From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique but re-reading this text before bed recently gave me a minor ‘aha’ moment. It resonated with my reading of Fiona Macdonald’s practice and in particular those projects that have been hosted by artist-run initiatives (ARI) over the last 18 years. So, the aha moment: as long as I can remember my parents have had a friend (theia Pitsa) who enjoys a good argument to such a degree I’m beginning to think disputation is the condition of their friendship. This redoubtable woman has been visiting may parents all my life – 30 years – and in that time there has been hardly a polite chat or moment of diplomatic commentary. However, their fighting isn’t about aggression but about creating psychological space for the development of astute ideological positions that must sit against or slightly askew from one another. It’s not obstinance so much as a forceful play. Like the institution of the ‘loyal opposition’ that incorporates dissent into the constitution of parliamentary government, theia Pitsa plays the part of the invited provocateur. I was thinking also how the redrawing of artistic tropes could itself be an act of light critique. By now it’s cuddle time and I’m sharing these thoughts with my partner who out-earnests me with the observation that art institutions’ ultimate incorporation and nurturing of art-that-critiques-art-institutions is an almost farcical illustration of what Anthony Giddens termed the ‘recursive character’ of social life. It illustrates the inevitability that dissent can’t break from structural features, but can only hope to tweak the social conditions of its creation even as it reproduces them. At this point I suggested to Jon (the partner) that from now on Giddens-like carbohydrates would be banned after 8pm. In the moments before lights-out I wanted space to familiarise myself with the evocative material fictions that Macdonald explored in ARIs – Store 5, Penthouse and Pavement and CLUBSproject. These have as much to do with how banality turns into humour, visceral body relations and seductive spatial arrangements, as they do with critique and its ramifications. ↩

In Melbourne in 2008, there’s ample material that explores the formation, organisation and ethos of artist-run initiatives but little artistic practice or commentary that allows space for critical reflexivity. This is not to say that there aren’t budding organisations ready to represent divergent perspectives; festivals highlighting their contribution to the creative (and not so creative) economies of the city, essays that explore historical lineages, lifestyles, real estate gentrifications and stories of independence as seen from a ‘grass roots’ arts organisation. Some would argue that site specificity embeds critical reflexivity into the form of a work. But often the rhetoric of site-specificity amounts to little more than a response to a window, the dominant floor patterning or the height of a wall – interesting sometimes, but moves that don’t exactly expose the ideological foundations or socio-political contexts that are equal parts of any ARI’s make-up. There are of course notable exceptions including: Lisa Kelly’s Servile Youth, a contribution to Sydney based Elastic publication that explored ARIs in relation to art writing, careerism and commercial enterprise; Keith Wong’s forensic accounting at Trocadero; and Anthony Gardener’s somewhat psychoanalytic and regrettable account (in the mode of a tabloid) produced for Un magazine, of Mike Canole’s work at CLUBSproject . These exercises variously interrogate the institution of the ARI and canvas broader social and economic interests via engagement with artists’ place in a public domain. Fiona Macdonald’s projects sit among, and standout from, the prevailing published accounts detailing the ethic of independent production; the rejection of the paradigm in which ARIs are viewed as rungs in the art world ladder of opportunity; the grouping of stylistic modalities that are reminiscent of the cool posturing of a reputable fashion magazines; and overviews of rent and real estate that sit somewhere between small business enterprise newsletter and a boutique’s public relations. There’s no questioning the sincerity of these texts, and the rich history of ARIs embracing practices that refer (aspirationally) to the avant-garde tendencies that are the core business of those other better funded institutions (think Russian Constructivism, Minimalism and Fluxus). However, in these particular projects Macdonald chooses to use the languages available to her in the sites in which she works. ↩

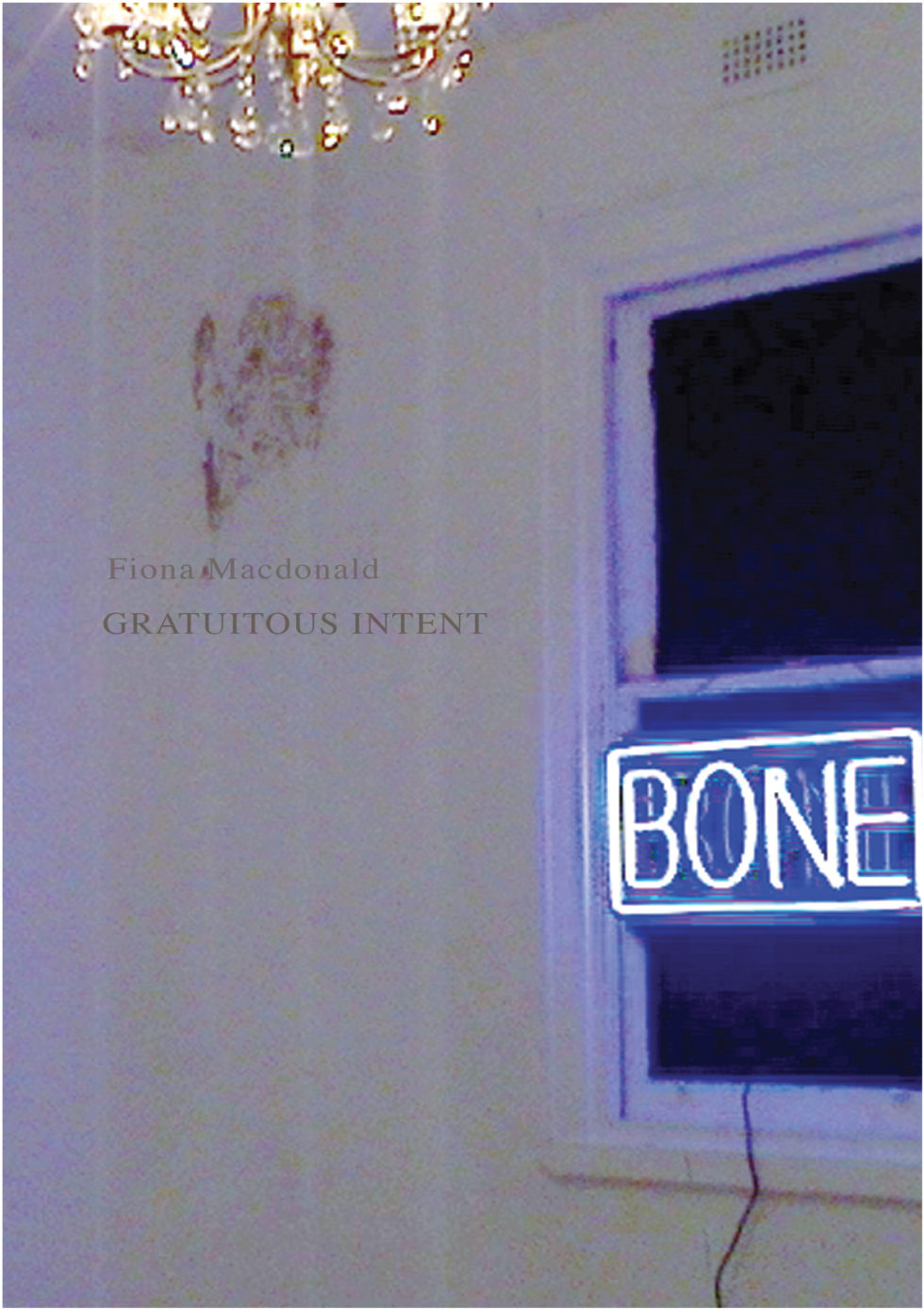

Hidden/Modern, Gratuitous and Bone are three different projects that occupy three distinct architectural configurations. And while I’m at pains to differentiate between the three projects under discussion and their respective ARI hosting architecture – it’s interesting to note that they had (and have) a similar position on open-call proposals: i.e. they don’t have them. Instead they chose alternative modes of procuring projects. Not wanting to risk this textual response to the pile of ARI administrative navel-gazing, it might be worthwhile pinpointing how Fiona Macdonald reprograms the audience’s experiential engagement of these spaces. Conversant with the conventions of how the respective ARI’s architecture host art practices, Macdonald places obstacles that interrupt any sense that this is business as usual. Hidden/Modern signposted (with a wall panel) the existence of a probable painting in Store 5 but this feature was in fact missing – the work revealed not a physical object but an allusion to the practices Store 5’s architecture supported and the historical avant-gardes that were their footnotes. In Gratuitous Macdonald placed a somewhat abstract painting that related frontally to the shop window and the pavement. Reflecting the mid-90s gallery practice of mimicking a corporate foyer, this single painting was accessorised with a pot plant and a brochure dispenser. Only the plant was awkwardly placed and not situated politely in the margins of the space and the painting wasn’t coolly hard edged and painted in gouache but showed signs of process that were tentative and slight. With the motto that ‘you can never over-accessorise,’ Macdonald accompanies the painting with lifestyle/fashion prints of the local ‘scene’ only to splodge them with artful and expressive gestures. What predictably would be a representation of critical conceptualism via the age-old artist’s guise of disingenuity was turned into something else – something more complicated than straight critique. At CLUBS provisional objects placements and relations abounded, but these relations were faint representational echoes of hyped-up sexuality, not the (righteous, sanctimonious or pedagogical) collaborative promiscuity that Bourriaud, Obrist and co. rally behind.

Store 5, Penthouse and Pavement and CLUBSproject don’t occupy the architectural spaces that Macdonald’s aforementioned projects took place in. In fact Store 5 and Penthouse and Pavement don’t function and CLUBS (at the time of writing) is in the process of a slow, managed dissolution. Store 5 was placed in a cryogenic chamber in 1993, and thawed recently into a series of commercial and museological exhibitions that established its historical influence and authority on Melbourne’s art community. Penthouse and Pavement has been just pavement with a shop window since 2003. The window, although mostly frosted, reveals a band of domesticity that is reminiscent of Dutch residential living. CLUBSproject along with the other seven galleries on Gertrude Street contributed to the gentrification of the area. While we loved the good coffee and the designer pizza, it created a neighbourhood that could no longer sustain non-commercial activity that wasn’t going to bring home the proverbial bacon for our landlords. I’m wondering whether the defunct status of all three ARIs somehow moves these buildings to some kind of ‘outside.’ Has letting go of the artistic burden for self-reflexivity allowed these spaces to meld back into the non-descript pockets of their localised landscapes? Would it be interesting to look at these pieces of architecture outside of their historical function as an ARI? Or not? Much has been said of the erasure of institutions’ inside/outside dichotomy and the instituting of art within the very critical frameworks that Macdonald works in – the “there’s no outside” talk. Macdonald continually investigates the evolving modes of ‘institutional critique’ outside of the historically specific period that this label connotes. Yet, I would say that it’s limiting to use Institutional Critique as the dominant Art Historical discursive lens through which to view these practices. It burdens them with expectations and obscures idiosyncrasies. While ARIs, the ex-ARI-buildings, Art History and for that matter this text are well and truly stuck inside the institution – these artists’ practices are functioning outside the parameters of Institutional Critique. Some would call this quality jouissance but fancy French words get me into theoretical trouble. It’s safer to apply fictions, funnies and fannies especially when commenting on Macdonald’s movement away from what Fraser would frame as the melancholia inherent in Institutional Critique. This melancholia resides when we realise that “we are the institutions of art: the object of our critiques, our attacks, is always also inside ourselves.” But I would say that Macdonald and co. (and that includes Fraser whom I am quoting) are not “blind…to the tragedy of (their) artistic present” but are making narratives through the production of new spaces out of old. They have treated the aforementioned diagnosed depression and have got on with the job. They have created narratives that are experienced through the humour of the prank, the scowl of the piss-take and the salacious transcription of, say, amateur porn. If this type of practice is, as Fraser claims, melancholic then I would like to complicate things further by stating that these practices have had enough therapy to know that self-deprecation is a perfectly effective strategy for making new narratives. For all my cynical posturing regarding the positions of the ARI, it is Store 5, Penthouse and Pavement and CLUBSproject that have invited Fiona Macdonald to perform a stocktake on their modes of practice and present something that lifts us through that so-called “tragedy of the our artistic present.” And while the ARIs get some kudos along the way, Fiona Macdonald signs no waiver. ↩